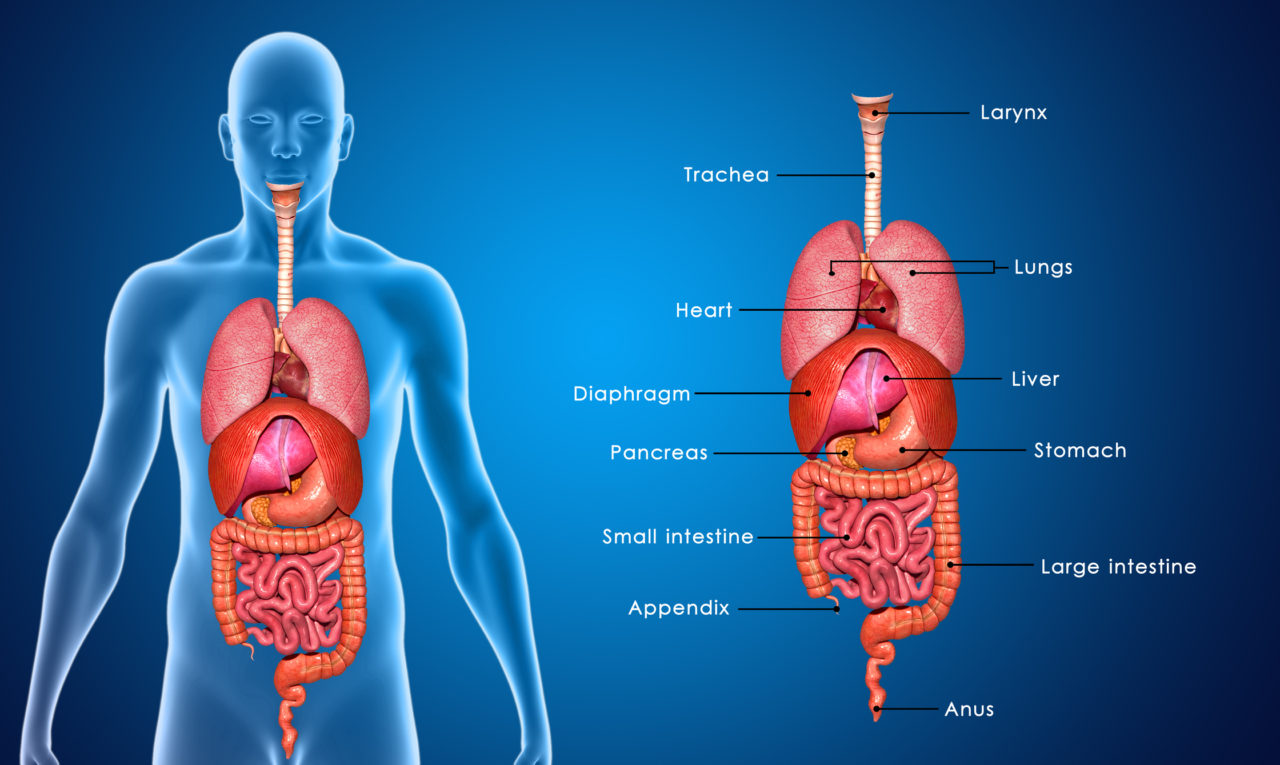

The Gastrointestinal Tract:

Being “balanced” depends so much on eating the right foods, being able to digest them, and the body’s ability to absorb these nutrients. Having an understanding of how digestion works, hopefully will lead you to make better food choices. I have learned this process under the Western ideals but also from an Ᾱyurvedic point of view. You know I am crazy about anatomy, so sit back and enjoy first the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract, the next blog which will be about the process of digestion itself, and then how Ᾱyurveda views digestion.

The gastrointestinal tract is a muscular tube that extends from the mouth, through the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum to the anus. Sometimes it is said to actually be on the outside of the body. The inside of this tract is called the lumen, and is continuous from one end to the other. The process of digestion begins in the mouth. As you chew your food, pieces of food are crushed into smaller pieces and fluids from foods, beverages and salivary glands blend with these pieces to ease swallowing. When stimulated, the taste buds detect one, or a combination of the 6 tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, astringent and pungent. In addition to these chemical triggers, aroma, texture and temperature also affect a foods flavor (the sense of smell is thousands of times more sensitive than the sense of taste).

The tongue allows you to taste food but also moves food around the mouth, facilitating chewing and swallowing. Swallowing is a reflex response initiated by a voluntary action and regulated by the swallowing center in the medulla of the brain. After swallowing, food is passed through the pharynx, a short tube that is shared by both the digestive system and the respiratory system. The epiglottis (an elastic cartilage at the back of the throat) closes off the air passages that are entrances to your lungs so that you don’t choke when you swallow. The food, once it has been swallowed is referred to as the bolus.

At this point in digestion, much of what happens is not consciously experienced. The muscles of the digestive tract meet internal needs without any effort on your part. They keep things moving, at just the right pace; slow enough to get the job done and fast enough to make progress.

Esophagus to the Stomach:

The esophagus has a sphincter muscle at each end. (A sphincter is a muscle that is able to form a ring that can contract or close a bodily opening, somewhat like a “drawstring” works). During a swallow, the upper esophageal sphincter opens allowing the bolus to slide down the esophagus, which passes through a hole in the diaphragm (a muscle that separates the thoracic cavity from the lower abdominopelvic cavity) to the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter at the entrance to the stomach closes behind the bolus so that it continues to move downward and doesn’t slip back up into the esophagus. It is this lower esophageal sphincter, sometimes called the cardiac sphincter because of its proximity to the heart, that prevents reflux of the stomach contents. The bolus remains in the upper portion of the stomach (the cardia region) for a while and then little by little, the food is transferred to the three other parts of the stomach: the fundus (which lies adjacent to the and above the cardia), the large central region called the body (the stomachs primary reservoir for swallowed food and its main production site for gastric juices) and then to the antrum or distal pyloric (the lowest portion which is one third of the entire stomach), as juices are added to it. As the bolus is ground up in the stomach it becomes a semiliquid mass called chyme.

An action called peristalsis, where the circular muscles that line the GI tract contract and relax, occurs continuously and pushes the contents along, beginning in the esophagus and continuing to the anus. When food is present in the GI tract, these contractions come in waves, varying in speed. For instance in the stomach, they occur three times per minute. While this is occurring, the stomach wall releases gastric juices. When the chyme is completely liquefied, the stomach releases the chyme through the pyloric sphincter, which opens briefly, about three times a minute (but really depending on the digestibility of the food being digested), to allow small portions to pass through into the small intestine. This sphincter also prevents the intestinal contents from backing up into the stomach.

Small Intestine:

At the beginning of the small intestine the chyme passes the opening from the common bile duct, which drips fluid into the small intestine from two organs outside the GI Tract, the gall bladder and the pancreas. Peristalsis now speeds up to ten times per minute once the chyme enters the small intestine. Segmentation, which is a periodic squeezing or partitioning of the intestine at intervals along its length by its circular muscles, promotes close contact of the chyme with the digestive juices and the absorbing cells of the intestinal walls. The chyme travels on down the small intestine through its three segments, the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum, almost 10 feet of tubing coiled within the abdomen. (Just too interesting to leave out—at death, when the muscles of the small intestine are relaxed and elongated, the small intestine is almost 2 ½ time longer or 25 feet long.)

Large Intestine:

The remaining contents, having traveled the length of the small intestine arrive at yet another sphincter, the ileocecal valve, at the beginning of the large intestine (colon) in the lower right side of the abdomen. Upon entering the colon, the contents pass another opening. Intestinal content which might happen to slip into this opening would end up in the appendix, a blind sac about the size of our little finger. The contents that bypass this opening travel through the large intestine up the right side of the abdomen (the ascending colon), across the top (transverse colon) to the left side, and down the lower left side (descending colon) and finally below the other folds of intestines to the back of the body above the rectum (sigmoid colon).

There are two other sphincter muscles worth mentioning, both of which control the anus, the involuntary internal anal sphincter and the voluntary external anal sphincter. Along with the tightness of the rectal muscle (which is a type of safety valve) they help prevent elimination until you choose to perform it voluntarily.