Hi, If you are just joining me on my adventure, please check out the previous blog. For those of you who’ve already read the first blog of this series, welcome back.

After we left Akshardham, we headed for Red Fort.

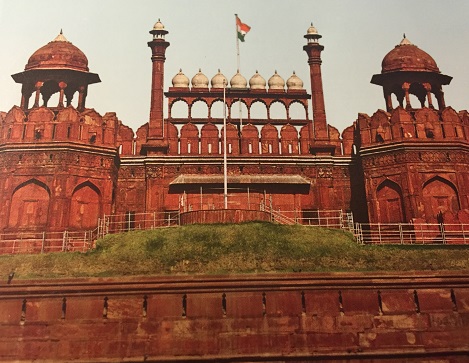

Red Fort is one of the most magnificent fort-palaces in India. Declared as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007, it served as the citadel of Shahjahanabad-the capital of the Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan (1628-1658) and the 5th in a line of only 6 Mughal rulers. It derives its name from the massive red sandstone walls. (Picture by UNESCO World Heritage Series) Inscription on the list of World Heritage sites confirms the universal value of a cultural or natural site which deserves protection for the benefit of all humanity. Almost every site I visited on this trip is on their list.

The fort consists of several palaces-significantly, Diwan-i-Am, Mumtaz-Mahal, Rang-Mahal, Khas-Mahal and Diwan-i-Khas-set amidst sprawling gardens. This is a picture of the moot that surrounded the fort which at one time was filled with alligators!

The Red Fort stands testimony to Mughal architectural excellence, which reached its zenith under Shah Jahan. Although based on Islamic guidelines, the plan reveals a fusion of Persian, Timurid and Hindu traditions. The Red Forts innovative planning and architectural style strongly influenced later structures in Rajasthan, Agra and other places.

It underwent a sea of change during the Uprising of 1857 and the subsequent British occupation. Today, the Mughal and British structures stand together in perfect symphony-a culmination of two distinct phases of Indian history.

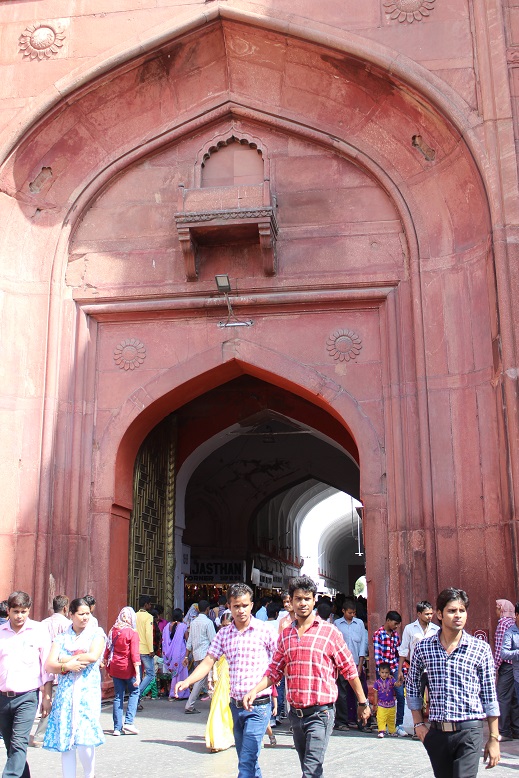

Lahori Gate is perhaps the most significant gateway of the Red Fort. Standing in the center of the west wall, facing Chandni-Chowk, it serves as the principal and ceremonial entrance.

After passing through the gates you enter Chhatta-Chowk. This long vaulted aisle lined with shops, and selling a range of exquisite handicrafts. It is also known as Meena Bazaar. The arcade was built to serve as the main market-pace for the women of the court. It opens to a central courtyard looking on to the Naubat-Khana, which subsequently leads on to the Diwan-i-am.

Muhammad Salih records that a building like this vaulted market had never been seen before by the people of India, as bazaars in seventeenth century India were normally held in the open. It is said that the Chhatta-Chowk bazaar owed its conception to Shah Jahan, who was greatly impressed with the concept of a covered market as it seemed very suitable for the hot climate of Delhi.

Originally the 32 cells on the ground floor on both sides of the passage consisted of two rooms, the front one used for display and the one at the back possibly being used for storage, or fabrication. The upper cells were perhaps used for business transactions.

Following 1857 these were used to house British army soldiers. Another story that our guide told us was that in the upper level the royal ladies would view the goods and then send their servants down to purchase the articles. With craftsmen and traders coming from across the world, the best and the most beautiful articles were on display here, exclusively for the ladies of royal households, precious stones and ornate jewelry; luxurious silks and brocades; gold and silver utensils, intricate wood and ivory carvings; brass and copper wares; arms and armaments and exotic spices. Of course Jane and I wanted to shop, but Navine would not have it as there was too much to show us and not enough time…I guess he has had practice letting clients shop only to run out of time LOL.

The Naubat-Khana (Drum House)

The Naubat-Khana stands at the entrance of the palace area, reached just after crossing the Chhatta-Chowk. It was used for playing drums five times a day at propitious hours, and also formed the formal entry to the forecourt of Diwan-i-Am. Known also as Hathipol, as all visitors were supposed to dismount there from their elephants (hathi) and walk towards the Diwan-i-AM. The only ones that could pass through this entrance mounted were Princes of the Blood Royal; everyone else had to dismount and walk from here.

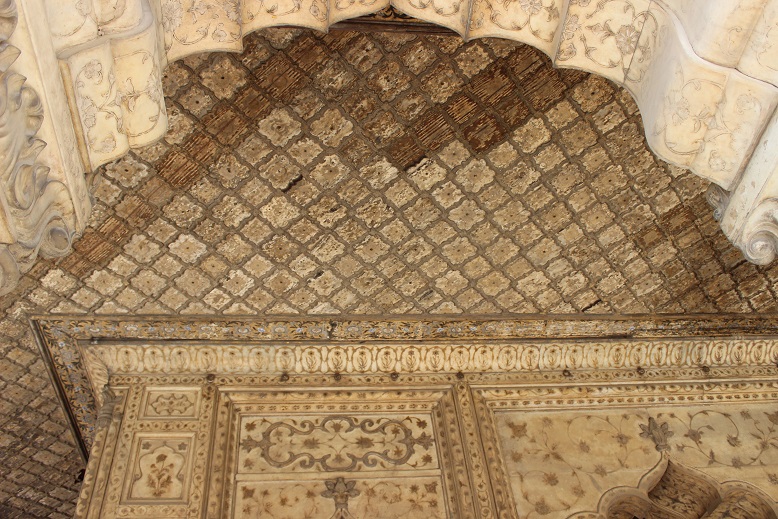

After the 1857 uprising, the building was used to house British Soldiers. (Above is a picture of the front side. Very plain.)

The backside or the side the Royals would see was much more beautiful with carvings of flowers and vines. Especially flowers, but also vines, were the influence of the Persians. The Mughals had not brought their artisans to India yet. (This is a picture of the backside)

On our way down the path to Diwan-I-Am and the other palaces we were both stopped by the beauty of this old banyan tree.

It was huge and its trunk and root system was amazing. Navine laughed and said that there were much bigger banyan trees, but he could appreciate our curiosity about this lovely tree.

Diwan-I-Am

Diwan-I-Am or the hall of public audience is one of the most striking buildings in the Red Fort. Reached after passing through the Naubat-Khana, this great hall is built of red sandstone and the central feature of the eastern side of the Red Fort. At one time it was covered with an overlay of shell plaster, ivory polished to give it a statelier look, like the marble palaces with which it was connected.

Set in the recess in the center of the back wall is a splendid marble canopy known as the Nashiman-i-Zill-i-Ilahi or the seat of the shadow of God. With its fluted columns, Bengal roof, and inlay of precious stones, this canopy stood over the emperor’s throne.

At the back of the canopy, the marble wall is decorated with the most exquisite patterns in multi-colored stones in “pietra dura”, by the Florentine jeweler, Austin de Bordeaux. He is said to have been employed by the emperor Shah Jahan both on the palaces in Red Fort as well as on the Taj in Agra.

The Palaces

Rang Mahal-The Palace of Color

This structure consists of a large central hall with arches set on piers, wand two smaller, vaulted chambers at either end. The central hall rests on a basement. The interiors of the main hall are divided into fifteen bays formed by intersecting arches each about 6m square. The eastern wall of Rang-Mahal is pierced by five jail windows which once overlooked the river. From here, the ladies of the zanana could catch a glimpse of the elephant fights which took place on the sandy beaches at the foot of the walls.

A marble water channel runs down from the center of Rang-Mahal from north to south, through which the Nahr-i-Bihisht flowed. In the center of the hall can be seen a marble basin, which is said to have been provided originally with an ivory fountains. Till as recently as 1908 this lay buried under a modern stone floor.

In the picture above you see the little tiny chambers in the marble was for candles. Al the water ran over from the top of this structure to the little pool below, the glow of the candles was reflected in the water. It must have been beautiful.

One can imagine the emperor seeking relief in the cool of the Rang-Mahal, resplendent with color and marble and musical with the subdued murmur of the falling waters and the voices of the chosen ladies.

Khas-Mahal

The Khas-Mahal was the emperor’s private palace. It consisted of three parts: Tasbih-Khana, Khwabgah and the Baithak.

In the middle, adjoining the Khwabgah (sleeping chamber) and overlooking the sandy banks of the Yamuna that once flowed close to the palace, is the domed balcony known as Muthamman-Burj, where the emperor appeared for his daily Darshan (public appearance). Animal fights including those between lions and elephants, were organized on the river banks, which could be viewed by the emperor and the royal ladies through the jali screens above. (In the picture of Navine and Jane. Yes Jane has on this funky head thing she created out of her scarf. It was so hot here and by wetting the scarf and wrapping it around her head, she said she stayed cooler!)

The Tasbih-Khana or chamber for telling beads, was used for private worship by the emperor. The three rooms behind it form the Khwabgah or sleeping chamber.

A beautiful marble screen separates the Tasbih-Khana from the Khwabgah. It is carved with the motif of a “Scale of Justice” suspended over a crescent moon and surrounded with stars. This motif is often repeated in the miniature paintings of Shah Jahan’s reign. Here you can also see the water way that ran through the palaces to keep them cool.

On the south end of Khas Mahal is a long hall, half the width of Khwabgah, known as the Baithak or sitting room, also known as the robe chamber. The Baithak has painted walls and ceiling and a perforated screen on the west.

Count Von Orlich, visiting Delhi in 1843, writes that, as they entered the halls which led to the kings chambers they saw a rhapsodist, who was sitting before the bed chamber of the ‘Great Mogul’ and relating tales in a loud voice. A simple curtain was hung between him and the king, who was lying on a couch and whom these tales were to lull to sleep. (Travels in India, Vol II, p.25)

Diwan-I-Khas

“If not the most beautiful, it is certainly the most highly ornamental of all Shahjahan’s buildings” This was James Fergusson describing the Diwan-I-Khas. Also known as Shah Mahal (royal palace), it was the emperor’s private audience hall, where he received his select ministers and noblemen of the highest ranks. Built entirely from polished white marble, the palace stood overlooking the river. Here Shah Jahan sat on his famed Peacock Throne, cooled by riverside breezes wafting through the windows, soft light reelection off the gilded ceilings and walls, and fine silk rugs strewn on the marble floor. Its decoration is the apogee of Mughal taste, a carefully balanced combination of opulence, extravagance and refinement.

The structure measures 27.4 m long (approximately 30 yards), 20.4 m wide (approximately 22 yards). Five engrailed arches rising on exquisitely adorned piers form the façade of Diwan-I-Khas. Similar intersecting arches divide the interiors into fifteen wide bays.

The lower part of the piers in the hall exhibit stunning pietra dura work, inlaid with mosaics (mostly floral patterns of carnelian, corals, lapis-lazuli and precious stones, while the upper portions wire gilded up to the ceiling.

As you can see the artwork is beautiful, known two piers decorated the same.

The decoration on the ceiling is highly praised by historians as well as by European travelers. Keene states that the original ceiling was made of silver, inlaid with gold, at a cost of RS 39 lakhs, which was looted and melted down by the Marathas in 1760. On a white marble foundation in the center of the Diwan-I-Khas sat the majestic Peacock Throne. It was so spectacular that a couplet referring to it holds, “the world had become so short of gold on account of it, that the purse of the earth was empty of treasury”.

The Hammam

To the north of Diwan-i-Khas lies the Hammam or the royal baths and the favorite resort of the Mughal Emperors, where important business decisions were also transacted. The baths consists of three chambers running east to west with intervening narrow aisles. All three chambers are equipped with tanks and fountains and boast of magnificent interiors. The marble floor and dados (the finishing of the lower part of an interior wall from floor to about waist height) are inlaid with colored stones, making floral pattern exhibiting the finest pietra dura work. Water flowed in channels that ran through these chambers over intricately carved flowers to create a fascinating impression of an indoor garden. One room was used only by children, one was specifically for the emperors and his ministers, and one was for steam baths that you can still see the holes in the floor where the steam came out. There was a dressing room. No longer can one visit inside the Hammam, so the above picture was taken by placing my lens through the iron bars on the windows…cool picture don’t you think?

Moti-Masjid

To the west of the Hammam is a small mosque, called the Moti-Masjid (pearl mosque), and built by Aurangzeb for his personal use. It gets its name from its sparkling white marble that glistens like pears in sunlight. Most of these types of places have their own mosques, quite like you find in Europe with chapels in people’s homes.

The grounds are really beautiful and the gardens are well maintained.

Many people visit, especially on weekends with their families, and I saw many of them enjoying picnics on the lawns. This lovely banyan tree offers some shade.

This building and an identical one are known as Sawan and Bhadon. These pavilions stand to the north and south of the Hayat-Bakhsh garden. They are named after the two months of the rainy season in the Hindu calendar.

These were once said to be highly ornnate, though the interiors are now bereft of any such decoration. You can still see where the candle holders are and again a stream of water flowed over them and created what I am sure was a beautiful glistening sight. These two pavilons were used to sit under when it rained and you could not sit in the garden.

In the background you can see two big buildings. Following the Uprising of 1857, 85 percent of the total fort area was taken over by the British. This changed the appearance of the complex considerably, as several existing Mughal structures were demolished, including the harem courts and gardens to the west of Rang-Mahal; the royal store-rooms and kitchens to the north of Diwan-i-Am, and the Mahtab-Bagh which once lay to the west of Hayat-Bakhsh garden. British buildings such as army barracks, hospitals, bungalows, administrative buildings, and sheds were built in their place.

As we are leaving, it is getting busier. It is Sunday and the kids are out of school. I was glad I could scratch off two of the main sites I wanted to see, but I needed a break from history and Navine delivered. You won’t believe what we get into next! Stay tuned, thanks for reading and sharing my adventure. Peggy