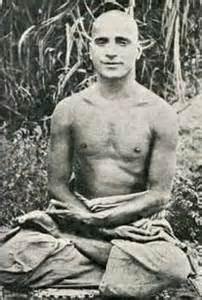

Yoga was first introduced in the United States in 1893 when Swami Vivekananda (to the left), a great Indian yogi, addressed the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, speaking to what is now known as jnana yoga, the yoga of knowledge.

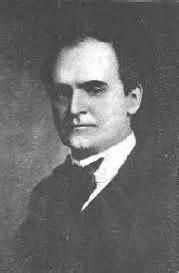

Yoga was first introduced in the United States in 1893 when Swami Vivekananda (to the left), a great Indian yogi, addressed the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, speaking to what is now known as jnana yoga, the yoga of knowledge. Next was Swami Rama Tirtha (to the right), an Indian teacher of the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta. He was among the first notable teachers of Hinduism to lecture in the United States travelling there in 1902. During his American tours Swami Rama Tirtha spoke frequently on the concept of practical Vedanta and education of Indian youth, proposing young students come to the United States to learn in the American Universities.

Next was Swami Rama Tirtha (to the right), an Indian teacher of the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta. He was among the first notable teachers of Hinduism to lecture in the United States travelling there in 1902. During his American tours Swami Rama Tirtha spoke frequently on the concept of practical Vedanta and education of Indian youth, proposing young students come to the United States to learn in the American Universities. In 1920, Yogananda Paramahansa (to the left) who is considered one of the preeminent spiritual figures of modern times came to the United States from India. He is sometimes referred to as the Father of Yoga in the West and was the first great master of yoga to actually live and teach in the West for an extended period of time (more than 30 years).

In 1920, Yogananda Paramahansa (to the left) who is considered one of the preeminent spiritual figures of modern times came to the United States from India. He is sometimes referred to as the Father of Yoga in the West and was the first great master of yoga to actually live and teach in the West for an extended period of time (more than 30 years).

Yogananda Paramahansa wrote the Autobiography of a Yogi, which is considered a spiritual classic. He founded the Self-Realization Fellowship (1920) and the Yogoda Satsanga Society of India (1917), which continue to carry on his spiritual legacy worldwide. Paramahansa Yogananda’s teachings include the science of Kriya Yoga meditation, the underlying unity of all true religions, and the art of balanced health and well-being in body, mind and soul.

William Walker Atkinson (to the right) was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1862. His interest in Hinduism and mysticism brought him to an exhibition in Chicago in 1893. It is believed that it was during this trip that Atkinson met Baba Bharata, a pupil of the late Indian mystic Yogi Ramacharaka (1799-1893). Bharata, who was very knowledgeable about yoga and Hinduism, had tried his hand at writing about these subjects but was unsuccessful. Atkinson, who was already a fine writer but knew little about those subjects, collaborated with Bharata and began writing under the pseudonym Yogi Ramacharaka. As Ramacharaka, he helped to popularize Eastern concepts in America, with yoga and a broadly-interpreted Hinduism being particular areas of focus. The over 200 works of Yogi Ramacharaka were published between 1903 and 1913, and became very popular by the 1920’s. He was best known for his books on the yogic breathing exercises known as pranayama.

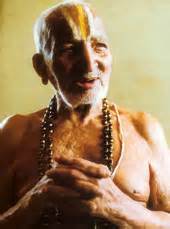

William Walker Atkinson (to the right) was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1862. His interest in Hinduism and mysticism brought him to an exhibition in Chicago in 1893. It is believed that it was during this trip that Atkinson met Baba Bharata, a pupil of the late Indian mystic Yogi Ramacharaka (1799-1893). Bharata, who was very knowledgeable about yoga and Hinduism, had tried his hand at writing about these subjects but was unsuccessful. Atkinson, who was already a fine writer but knew little about those subjects, collaborated with Bharata and began writing under the pseudonym Yogi Ramacharaka. As Ramacharaka, he helped to popularize Eastern concepts in America, with yoga and a broadly-interpreted Hinduism being particular areas of focus. The over 200 works of Yogi Ramacharaka were published between 1903 and 1913, and became very popular by the 1920’s. He was best known for his books on the yogic breathing exercises known as pranayama. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (to the left) was an Indian guru (teacher of spirituality). He was most famous for his development of Transcendental Meditation. The Maharishi began what he called the “Spiritual Regeneration Movement” in 1958. He traveled around the world, teaching Transcendental Meditation to ordinary people. He also was well known for his association with rock bands including the Beatles and the Beach Boys.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (to the left) was an Indian guru (teacher of spirituality). He was most famous for his development of Transcendental Meditation. The Maharishi began what he called the “Spiritual Regeneration Movement” in 1958. He traveled around the world, teaching Transcendental Meditation to ordinary people. He also was well known for his association with rock bands including the Beatles and the Beach Boys.

In 1966, Swami Prabhupada (to the right), founded the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), commonly known as the “Hare Krishna Movement“. He emerged as a major figure of the Western counterculture, initiating thousands of young Americans. Despite attacks from anti-cult groups, he received a favorable welcome from many religious scholars.

By the end of the 1960’s the yoga movement, which up until now had failed to gather much interest in the United States, really began to pick up. Eastern spiritual and philosophical texts were being translated into English, which helped famous scholars kindle a growing awareness. People were becoming interested in Yoga, surmising that it came from a country predominately Hindu, but Yoga was not a Hindu religion and Yoga includes much more than just asana. Yoga styles such as Integral Yoga, Siddha Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, Dhyana Yoga, and Ashtanga Yoga were just some of the forms that had found their way west. (Yoga: The Legacy of the Sages, Pandit Rajmani Tigunait).

Many forms of yoga introduced by many learned yogis have found its way to America, but it’s Krishnamacharya, a man who would never visit the west, that is most well-known. Those who participate in asana practice in the United States today are most likely continuing his linage.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (to the left) was born on November 18, 1888, in a village in the state of Mysore, South India.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (to the left) was born on November 18, 1888, in a village in the state of Mysore, South India.

His linage traces back to the famous ninth century South Indian sage Nathamuni, author of the Yoga Rahasya and the first teacher in the line of Vaishnava (those devoted to worshiping Lord Vishnu) gurus.

As a child, Krishnamacharya studied yoga and Sanskrit from his father. His father’s family were well known advisors (similar to today’s prime ministers), sometimes advising even the kings. In order to advise, they needed the wisdom which came from reading and understanding the classic texts that describe the branches of the Vedas. Yoga was one of those branches and because Krishnamacharya’s family background was historically involved with yoga, Krishnamacharya also developed a special interest in the practice.

At the age of twelve, Krishnamacharya entered not one, but two respected schools: the Brahmin school, Brahmatanta Parakala Mutt (pictured above) in Mysore; and the Royal College of Mysore. He studied the Vedic texts and Vedic rituals and at age eighteen moved to Banaras (Varanasi or Kashi), to further his studies of Sanskrit, logic and grammar at the university. He returned to Mysore to study the philosophy of the Vedānta from Śrī Krishna Brahmatantra Swami, the director of the Parakala Mutt.

Vowing to study at only the best schools in India, Krishnamacharya found himself back in northern India, in the city of Banaras (Varanasi or Kashi) at Queens College, studying Sāmkhya, India’s oldest philosophical system and the one on which yoga is fundamentally based. Here he impressed a teacher named Ganganath-Jha who recommended he go to a great yoga teacher further north. Krishnamacharya obtained the permission and support of the Viceroy in Simla, Lord Irwin for this venture. In 1916, after two and a half months of walking, he arrived at the foot of Mount Kailash, in the Himalayas, where he met this teacher, Śrī Ramamohan Brahmachari, a yogi who was living with his family near Lake Manasarovar in Tibet.

Krishnamacharya was with his teacher for more than seven years. He studied the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, learning asana and pranayama, and studying the therapeutic aspects of yoga. At the end of his studies with the guru, Krishnamacharya asked what his payment would be. The master responded that Krishnamacharya was to take a wife, raise children and be a teacher of Yoga; however, Krishnamacharya chose to go back to southern India and study Ayurveda (the traditional Indian healing system) and the philosophy of Nyāya (a Vedic school of logic). He also studied the writings of some great yogis of Southern India referred to as Alvar, or “someone who has come to us to rule”. Alvar are not from Brahmin families but sometimes come from simple peasant families. Alvar, who are endowed with greatness as babies, direct the minds of other people and are regarded as an incarnation of God. It was through these studies that he was able to combine the knowledge from the great teachings of the north with the great teachings of the south.

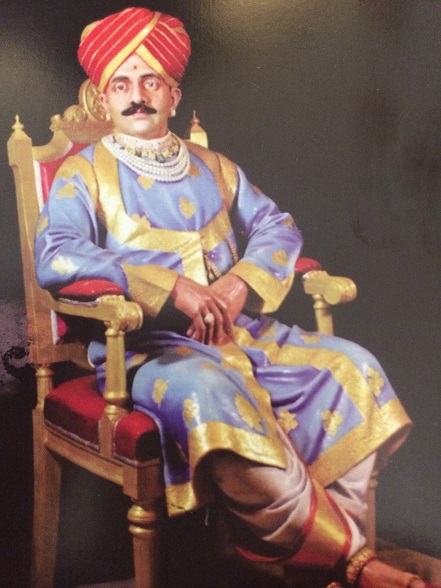

In 1925 Krishnamacharya married. He was forced by circumstance to work in a coffee plantation in the Hasan district. In 1931, Krishnamacharya gave a lecture in Mysore which eventually led the raja, Krishnarajendra Wodoyar IV, the mahārājah of Mysore (pictured above), to hire him to teach his family yoga and to work with him on his ailments. When Krishnamacharya was offered a teaching position at the Sanskrit College in Mysore, the Mahārājah asked Krishnamacharya to open a yoga school under his patronage. In 1933, The Yoga Shala, Krishnamacharya’s yoga school, opened in a wing of a nearby palace, the Jaganmohan Palace.

In 1925 Krishnamacharya married. He was forced by circumstance to work in a coffee plantation in the Hasan district. In 1931, Krishnamacharya gave a lecture in Mysore which eventually led the raja, Krishnarajendra Wodoyar IV, the mahārājah of Mysore (pictured above), to hire him to teach his family yoga and to work with him on his ailments. When Krishnamacharya was offered a teaching position at the Sanskrit College in Mysore, the Mahārājah asked Krishnamacharya to open a yoga school under his patronage. In 1933, The Yoga Shala, Krishnamacharya’s yoga school, opened in a wing of a nearby palace, the Jaganmohan Palace.

His connections with the mahārājah, along with his traveling through India giving yoga demonstrations, would lead to some interesting connections. He was soon to be written about by some of the students who had come to visit him, and these stories helped him gain popularity. This news spread through southern India and before too long he had students coming to him from all over the region and world.

In 1927 at the age of 12, Pattabhi Jois (to the left), the yogi responsible for popularizing Ashtanga Yoga, began to study with Krishnamacharya after attending one of the yoga demonstrations. He would eventually bring the Ashtanga Yoga style of yoga to the United States in 1975.

In 1927 at the age of 12, Pattabhi Jois (to the left), the yogi responsible for popularizing Ashtanga Yoga, began to study with Krishnamacharya after attending one of the yoga demonstrations. He would eventually bring the Ashtanga Yoga style of yoga to the United States in 1975.

In 1930, Krishnamacharya wrote a small book titled Yoga Makaranda (Honey of Yoga), in which he explained with considerable fluidity the system of vinyasa krama, what will eventually become the Vinyasa Yoga style of yoga.

In 1934, B.K.S.Iyengar (who was to become Krishnamacharya’s brother-in-law) began to study with him. (Pictured above) In 1970, Iyengar would visit the West introducing the Iyengar Yoga style.

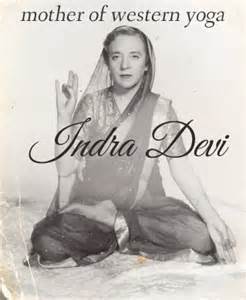

In 1934, B.K.S.Iyengar (who was to become Krishnamacharya’s brother-in-law) began to study with him. (Pictured above) In 1970, Iyengar would visit the West introducing the Iyengar Yoga style. In 1937, Indra Devi became Krishnamacharya’s first student from the west. Born Eugenie Peterson in Riga Latvia in 1899, she would use her stage name, Indra Devi to become a rising star in Indian films. Through her new husband, a commercial attaché

In 1937, Indra Devi became Krishnamacharya’s first student from the west. Born Eugenie Peterson in Riga Latvia in 1899, she would use her stage name, Indra Devi to become a rising star in Indian films. Through her new husband, a commercial attaché

to the Czechoslovak Consulate in Bombay, she metKrishnarajendra Wodoyar, the mahārājah of Mysore. Women in those days were not allowed to practice yoga. When Devi requested yoga lessons from Krishnamacharya, he refused to help her on the grounds that she was from the west and was a woman. It was the mahārājah that stepped in and granted Devi the privilege of learning from the great yoga master.

In 1947, Devi would open a yoga school in Beverly Hills. Many of her students were Hollywood actors and actresses. (picture: Devi with Krishnamacharya later in life)

In 1946, around the time that India gained independence, the powers of the mahārājahs were curtailed, and the funding for the yoga school was cut off. Krishnamacharya struggled to keep the school open. In 1950, on the orders of the first Chief Minister of Mysore State, the school closed. Krishnamacharya’s interest turned to treating the sick using Ayurveda and yoga as healing agents. In 1952 he was called to the city of Madras (Chennai) to treat a popular politician who had suffered a heart attack. Krishnamacharya finally settled in Madras with his family.

T.K.V. Desikachar, a famous yoga teacher in his own right, is Krishnamacharya’s son and closest disciple (to the left).

T.K.V. Desikachar, a famous yoga teacher in his own right, is Krishnamacharya’s son and closest disciple (to the left).

He founded the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, an institution where yoga is used to treat sick people. This institute is in Chennai and I hope to visit it on my trip to India in November.

Krishnamacharya was teaching and inspiring those around him until six weeks prior to his death in 1989. Unlike many of his famous students, he had never visited the United States.

According to Krishnamacharya’s son, Desikachar, the most important yoga text as far as his father was concerned was always Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra. Understanding the Yoga Sutra is a lifelong task. He wrote many commentaries on this text; his last one, between 1984-1986, contains thoughts he had never expressed before in other commentaries.

Each time the Yoga Sutra is read, more is revealed, something different comes to light. Whether discussing the body, the breath or the mind, The Yoga Sutra is an inspired text in all regards (The Heart of Yoga Developing a Personal Practice, T.K.V. Desikachar).

It has been a little over 100 years that Yoga has been in our country. Many more individuals than I have mentioned in this blog are responsible for bringing it to us. However, as you can see, many of the asana practices offered today in Yoga Studios, gyms, community centers, and under private instruction come from the linage of Krishnamacharya. Watch for upcoming blogs on the styles of Yoga Asana: Ashtanga, Iyengar, Vinyasa, Kundalini, Yin, etc.

Thanks for reading and please share these blogs with your friends. Namasté, Peggy